SIL Open Font License v1.10

- This is inspiring German Calligraphy Fonts design resource gallery. We take several hour to select these inspiring calligraphy font pictures from good graphic designer. Maybe, you haven't got these german gothic script font, german gothic font and old cursive handwriting before, we will see inspiring ideas to build the other graphic design.

- Looking for German fonts? Click to find the best 178 free fonts in the German style. Every font is free to download!

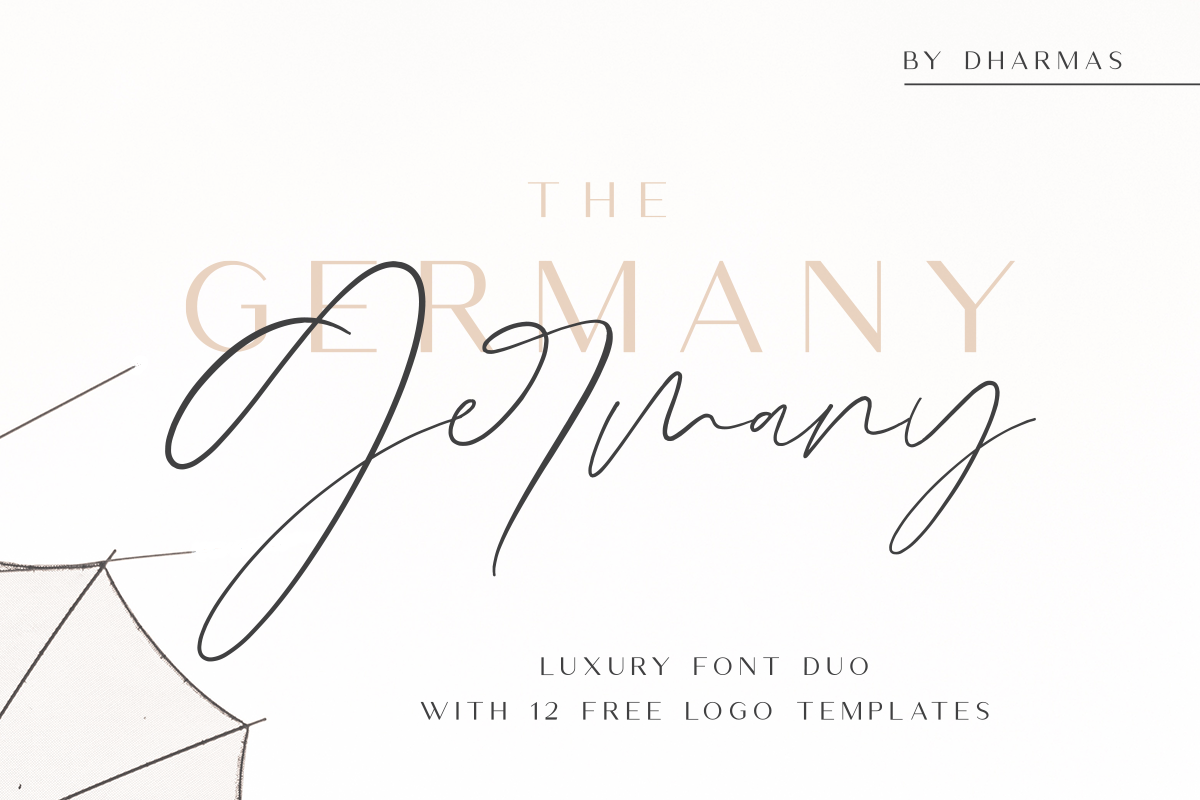

- Germany also includes a set of 12 editable logo templates, each one uniquely combining the two Germany fonts to create striking, modern logo designs for you to edit and use as your own. Thanks to dharmas. This is the demo version. Germany Font free for personal use, please visit his store for more other products, and buying fonts support him.

This license can also be found at this permalink: https://www.fontsquirrel.com/license/germania-one

Copyright (c) 2011, John Vargas Beltr�n (www.johnvargasbeltran.com|john.vargasbeltran@gmail.com),

with Reserved Font Name “Germania”.

This Font Software is licensed under the SIL Open Font License, Version 1.1.

This license is copied below, and is also available with a FAQ at: http://scripts.sil.org/OFL

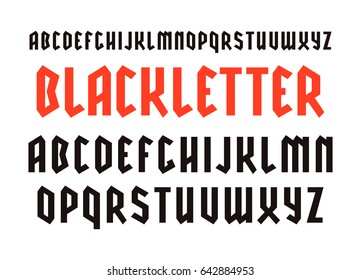

Today in Germany, blackletter typefaces are frequently used by Neo-Nazi groups and for many Germans, they bring to mind the dark times of the country’s fascist past. Florian Hardwig is a graphic designer and the editor of a website called Fonts in Use and he says that in Germany, any blackletter typeface is used to signal German nationalism. Check out our german font selection for the very best in unique or custom, handmade pieces from our digital shops.

—————————————————————————————-

SIL OPEN FONT LICENSE Version 1.1 - 26 February 2007

—————————————————————————————-

PREAMBLE

The goals of the Open Font License (OFL) are to stimulate worldwide development of collaborative font projects, to support the font creation efforts of academic and linguistic communities, and to provide a free and open framework in which fonts may be shared and improved in partnership with others.

The OFL allows the licensed fonts to be used, studied, modified and redistributed freely as long as they are not sold by themselves. The fonts, including any derivative works, can be bundled, embedded, redistributed and/or sold with any software provided that any reserved names are not used by derivative works. The fonts and derivatives, however, cannot be released under any other type of license. The requirement for fonts to remain under this license does not apply to any document created using the fonts or their derivatives.

DEFINITIONS

“Font Software” refers to the set of files released by the Copyright Holder(s) under this license and clearly marked as such. This may include source files, build scripts and documentation.

“Reserved Font Name” refers to any names specified as such after the copyright statement(s).

“Original Version” refers to the collection of Font Software components as distributed by the Copyright Holder(s).

“Modified Version” refers to any derivative made by adding to, deleting, or substituting—in part or in whole—any of the components of the Original Version, by changing formats or by porting the Font Software to a new environment.

“Author” refers to any designer, engineer, programmer, technical writer or other person who contributed to the Font Software.

PERMISSION & CONDITIONS

Permission is hereby granted, free of charge, to any person obtaining a copy of the Font Software, to use, study, copy, merge, embed, modify, redistribute, and sell modified and unmodified copies of the Font Software, subject to the following conditions:

1) Neither the Font Software nor any of its individual components, in Original or Modified Versions, may be sold by itself.

2) Original or Modified Versions of the Font Software may be bundled, redistributed and/or sold with any software, provided that each copy contains the above copyright notice and this license. These can be included either as stand-alone text files, human-readable headers or in the appropriate machine-readable metadata fields within text or binary files as long as those fields can be easily viewed by the user.

3) No Modified Version of the Font Software may use the Reserved Font Name(s) unless explicit written permission is granted by the corresponding Copyright Holder. This restriction only applies to the primary font name as presented to the users.

4) The name(s) of the Copyright Holder(s) or the Author(s) of the Font Software shall not be used to promote, endorse or advertise any Modified Version, except to acknowledge the contribution(s) of the Copyright Holder(s) and the Author(s) or with their explicit written permission.

5) The Font Software, modified or unmodified, in part or in whole, must be distributed entirely under this license, and must not be distributed under any other license. The requirement for fonts to remain under this license does not apply to any document created using the Font Software.

TERMINATION

This license becomes null and void if any of the above conditions are not met.

DISCLAIMER

THE FONT SOFTWARE IS PROVIDED “AS IS”, WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO ANY WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT OF COPYRIGHT, PATENT, TRADEMARK, OR OTHER RIGHT. IN NO EVENT SHALL THE COPYRIGHT HOLDER BE LIABLE FOR ANY CLAIM, DAMAGES OR OTHER LIABILITY, INCLUDING ANY GENERAL, SPECIAL, INDIRECT, INCIDENTAL, OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES, WHETHER IN AN ACTION OF CONTRACT, TORT OR OTHERWISE, ARISING FROM, OUT OF THE USE OR INABILITY TO USE THE FONT SOFTWARE OR FROM OTHER DEALINGS IN THE FONT SOFTWARE.

Nazi Germany Font

The Antiqua–Fraktur dispute was a typographical dispute in 19th- and early 20th-century Germany.

In most European countries, blacklettertypefaces like the German Fraktur were displaced with the creation of the Antiqua typefaces in the 15th and 16th centuries. However, in Germany, both fonts coexisted until the first half of the 20th century.

During that time, both typefaces gained ideological connotations in Germany, which led to long and heated disputes on what was the 'correct' typeface to use. The eventual outcome was that the Antiqua-type fonts won when the Nazi Party chose to phase out the more ornate-looking Fraktur.

Origin[edit]

Historically, the dispute originates in the differing use of these two typefaces in most intellectual texts. Whereas Fraktur was preferred for works written in German, for Latin texts, Antiqua-type typefaces were normally used. This extended even to English–German dictionaries. For example, the English words would all be written in Antiqua, and the German words in Fraktur. Originally this was simply a convention.

19th century[edit]

Conflict over the two typefaces first came to a head after the occupation of Germany and dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire by Napoleon in 1806, which led to a period in the history of Germany in which nationalists began to attempt to define what cultural values were common to all Germans. There was a massive effort to canonize the German national literature—for example, the Grimm Brothers' collection of fairy tales—and to create a unified German grammar.

In the context of these debates, the two typefaces became increasingly polarized: Antiqua typefaces were seen to be 'un-German', and they were seen to represent this by virtue of their connotations as 'shallow', 'light', and 'not serious'. In contrast, Fraktur, with its much darker and denser script, was viewed as representing the allegedly German virtues such as depth and sobriety.

During the Romantic Era, in which the Middle Ages were glorified, the Fraktur typefaces additionally gained the (historically incorrect) interpretation that they represented German Gothicism. For instance, Goethe's mother advised her son, who had taken to the clear Antiqua typefaces, to remain—'for God's sake'—German, even in his letters.

German Gothic Font

Otto von Bismarck was a keen supporter of German typefaces. He refused gifts of German books in Antiqua typefaces and returned them to sender with the statement Deutsche Bücher in lateinischen Buchstaben lese ich nicht! (I don't read German books in Latin letters!).[1]

20th century[edit]

The dispute between Antiqua and Fraktur continued well into the 20th century. Arguments for Fraktur were not only based on historical and cultural perceptions, but also on the claim that Fraktur was more suited for printing German and other Germanic languages, as their proponents claimed it to be more readable than Antiqua for this purpose.

A 1910 publication by Adolf Reinecke, Die deutsche Buchstabenschrift, claims the following advantages for using Fraktur as the German script:

- German script is a real reading script: it is more readable, i.e. the word images are clearer, than Latin script.[2]

- German script is more compact in printing, which is an advantage for fast recognition of word images while reading.

- German script is more suitable for expressing German language, as it is more adapted to the characteristics of the German language than the Latin script.

- German script does not cause nearsightedness and is healthier for the eyes than Latin script.[3]

- German script is still prone to development; Latin script is set in stone.

- German script can be read and understood all over the world, where it is actually often used as ornamental script.

- German script makes it easier for foreigners to understand the German language.[4]

- Latin script will gradually lose its position as international script through the progress of the Anglo-Saxon world (here the author states that 'Anglo-Saxons in the UK, the United States and Australia are still 'Germanic' enough to annihilate the Latin-scriptler's dream of a Latin 'world-script'').[5]

- The use of Latin script for German language will promote its infestation with foreign words.

- German script does not impede at all the proliferation of German language and German culture in other countries.

On 4 May 1911, a peak in the dispute was reached during a vote in the Reichstag. The Verein für Altschrift ('Association for Antiqua') had submitted a proposition to make Antiqua the official typeface (Fraktur had been the official typeface since the foundation of the German Empire) and no longer teach German Kurrent (blackletter cursive) in the schools. After a long and, in places, very emotional debate, the proposition was narrowly rejected 85–82.

Nazis had a complex and variable relationship with Fraktur. Adolf Hitler personally disliked the typeface. In fact, as early as 1934 he denounced its continued use in a speech to the Reichstag:[6]

Your alleged Gothic internalization does not fit well in this age of steel and iron, glass and concrete, of womanly beauty and manly strength, of head raised high and intention defiant ... In a hundred years, our language will be the European language. The nations of the east, the north and the west will, to communicate with us, learn our language. The prerequisite for this: The script called Gothic is replaced by the script we have called Latin so far ...

Nonetheless, Fraktur typefaces were particularly heavily used during the early years of the National Socialist era, when they were initially represented as true German script. In fact, the press was scolded for its frequent use of 'Roman characters' under 'Jewish influence', and German émigrés were urged to use only 'German script'.[7] However Hitler's distaste for the script saw it officially discontinued in 1941 in a Schrifterlass ('edict on script') signed by Martin Bormann.[8]

One of the motivations seems to have been compatibility with other European languages. The edict mentions publications destined for foreign countries, Antiqua would be more legible to those living in the occupied areas; the impetus for a rapid change in policy probably came from Joseph Goebbels and his Propaganda Ministry.[9] Readers outside German-speaking countries were largely unfamiliar with Fraktur typefaces. Foreign fonts and machinery could be used for the production of propaganda and other materials in local languages, but not so easily in German as long as the official preference for Fraktur remained.

Bormann's edict of 3 January 1941 at first forbade only the use of blackletter typefaces. A second memorandum banned the use of Kurrent handwriting, including Sütterlin, which had only been introduced in the 1920s. From the academic year 1941/42 onwards, only the so-called Normalschrift ('normal script'), which had hitherto been taught alongside Sütterlin under the name of 'Latin script', was allowed to be used and taught, Kurrent did remain in use until 1945 for some applications such as cloth military insignia badges.

After the Second World War[edit]

After the Second World War, the Sütterlin script was once again taught in the schools of some German states as an additional script, but it could not hold out against the usage of Latin cursive scripts. Nowadays, since few people who can read Kurrent remain, most old letters, diaries, etc. remain inaccessible for all but the most elderly German speakers. As a consequence, most German-speaking people today find it difficult to decipher their own parents' or grandparents' letters, diaries, or certificates.

However, the Fraktur script remains present in everyday life in some pub signs, beer brands and other forms of advertisement, where it is used to convey a certain sense of rusticity and oldness. However, the letterforms used in many of these more recent applications deviate from the traditional letterforms, specifically in the frequent untraditional use of the round s instead of the long s (ſ) at the beginning of a syllable, the omission of ligatures, and the use of letter-forms more similar to Antiqua for certain especially hard-to-read Fraktur letters such as k. Books wholly written in Fraktur are nowadays read mostly for particular interests. Since many people have difficulty understanding blackletter, they may have trouble accessing older editions of literary works in German.

A few organizations such as the Bund für deutsche Schrift und Sprache continue to advocate the use of Fraktur typefaces, highlighting their cultural and historical heritage and their advantages when used for printing Germanic languages. But these organizations are small, somewhat sectarian, and not particularly well known in Germany.

In the United States, Mexico, and Central America, Old Order Amish, Old Order Mennonite, and Old Colony Mennonite schools still teach the Kurrent handwriting and Fraktur script. German books printed by Amish and Mennonite printers use the Fraktur script.

German Type Font

References[edit]

- ^Adolf Reinecke, Die deutsche Buchstabenschrift: ihre Entstehung und Entwicklung, ihre Zweckmäßigkeit und völkische Bedeutung, Leipzig, Hasert, 1910, p. 79.

- ^Reinecke, pp. 42, 44.

- ^Reinecke, pp. 42, 49.

- ^Reinecke, pp. 58–59.

- ^Reinecke, p. 62.

- ^from Völkischer Beobachter Issue 250, 7 September 1934.

- ^Eric Michaud, The Cult of Art in Nazi Germany, tr. Janet Lloyd, Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2004, ISBN9780804743266, pp. 215–16 and Plate 110.

- ^Facsimile of Bormann's Memorandum (in German)

The memorandum itself is typed in Antiqua, but the NSDAPletterhead is printed in Fraktur.

'For general attention, on behalf of the Führer, I make the following announcement:

It is wrong to regard or to describe the so-called Gothic script as a German script. In reality, the so-called Gothic script consists of Schwabach Jew letters. Just as they later took control of the newspapers, upon the introduction of printing the Jews residing in Germany took control of the printing presses and thus in Germany the Schwabach Jew letters were forcefully introduced.

Today the Führer, talking with Herr ReichsleiterAmann and Herr Book Publisher Adolf Müller, has decided that in the future the Antiqua script is to be described as normal script. All printed materials are to be gradually converted to this normal script. As soon as is feasible in terms of textbooks, only the normal script will be taught in village and state schools.

The use of the Schwabach Jew letters by officials will in future cease; appointment certifications for functionaries, street signs, and so forth will in future be produced only in normal script.

On behalf of the Führer, Herr Reichsleiter Amann will in future convert those newspapers and periodicals that already have foreign distribution, or whose foreign distribution is desired, to normal script'.

- ^Michaud, pp. 216–17.

Oktoberfest Font Styles

Further reading[edit]

- Silvia Hartmann: Fraktur oder Antiqua: der Schriftstreit von 1881 bis 1941. Lang, Frankfurt am Main u.a. 1998, ISBN3-631-33050-2

- Christina Killius: Die Antiqua-Fraktur Debatte um 1800 und ihre historische Herleitung. Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden, 1999, ISBN3-447-03614-1

- Albert Kapr: Fraktur, Form und Geschichte der gebrochenen Schriften. Verlag Hermann Schmidt, Mainz 1993, ISBN3-87439-260-0

External links[edit]

- Die Nationalsozialisten und die Fraktur (in German)

- Bund für deutsche Schrift und Sprache (in German)

This article incorporates text translated from the corresponding German Wikipedia article as of December 2005.

Font Germany 2014